The Fragmented Child: Disorganized Attachment and Dissociation

Dissociation is a phenomenon most people have the capacity to experience. It is a coping mechanism used to manage stressors as minor as over-stimulation or as severe as sexual abuse.

As a way of coping, dissociation occurs when the brain compartmentalizes traumatic experiences to keep people from feeling too much pain, be it physical, emotional, or both. When dissociation occurs, you experience a detachment from reality, like ‘spacing out.’ Part of you just isn’t ‘there in the moment.’

Children who suffer from problematic dissociation can often display symptoms that can be misinterpreted as other psychological problems. According to the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation, children with dissociative disorders are prone to trance states or ‘black outs’ where the child becomes unresponsive or has a lapse in attention. They may also stare at nothing, forget parts of their life or what they were doing a moment ago, or act as if they just woke up in response to being called to attention. Coupled with sudden changes in activity levels (like a child being lethargic one minute and hyperactive the next), these symptoms are often misinterpreted as Attention Deficit Disorder or Bipolar Disorder.

Other dissociative symptoms like dramatic, abnormal changes in mood, personality, or age, acting in socially inappropriate ways, or insisting on being called by another name can also lead to misdiagnoses of psychotic or behavioural disorders.

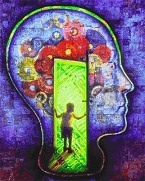

Underlying all of these symptoms is a tendency for the child to separate parts of themselves, or ‘fragment.’ This fragmentation is often the result of already experienced trauma. In children, the traumatic situation is often a form of abuse or neglect in the home, either as a witness or victim.

Though no single cause that has been identified explaining the phenomenon of dissociation, it is believed by some clinicians that the attachments formed between the child and their caregiver could play a substantial role in the risk of developing dissociative symptoms.

In attachment theory, the caregiver ideally serves as a secure base from which the child can receive comfort and support (secure attachment). Their responses to the child’s actions determine how the child will come to see the world and view relationships in the future. One particular form of attachment, disorganized attachment occurs when the caregiver mistreats the child, frequently frightens the child, miscommunicates feelings, and has highly unrealistic expectations of the child (e.g., relying on the child for care).

Caregivers who act in ways that give rise to disorganized attachment may behave very inconsistently (for example at times they are intrusive, at times they withdraw), which creates confusion for the child. The child may end up with multiple, incompatible views of the caregiver (seeing the caregiver as a source of protection and danger at the same time) and incompatible views of themselves (feeling confusion about whether they are good or bad). These incompatible views are very difficult to reconcile and hard to combine into a coherent structure.

The child is left with confusion about who their parents are, and who they are, making it difficult to establish a coherent sense of self. This sort of fragmentation lays the groundwork for dissociative experiences.

Even more confusing, the child faces the dilemma of both protecting themselves from a caregiver and maintaining a relationship with them. Jennifer Freyd explains that the betrayal trauma, the sense of betrayal often found in children abused by their caregivers explains why many children forget the abuse, or rather, put it out of their minds.

If the child copes by dissociating, it makes it easier to continue daily life with the parent than if they were fully aware of the traumatic past experiences.

Sadly, many parents who create conditions that give rise to disorganized attachment do so because they experienced maltreatment in their own childhoods. University of Maryland researchers Jude Cassidy and Jonathon J. Mohr’s findings suggest that in addition to being correlated with dissociative disorders, disorganized attachment has also been shown to be related to trauma in childhood.

Additionally, researchers Paolo Pasquini and Giovanni Liotti of The Italian Group for the Study of Dissociation found that mothers who experience a stressful or traumatic event within the first two years of the child’s life have an increased chance that the child will have dissociative symptoms and a disorganized attachment style.

Caregivers at risk can help prevent such developments in their children by participating in therapy designed to examine and resolve traumas experienced in their past. Psychotherapy can also help teach parents how to interact with their children in a consistent and responsive way, and control their emotions to prevent harmful actions.

In this way, it is possible to not only help the adult come to terms with their childhood experiences, but also help create a healthy family environment for the child’s future.

-Jennifer Parlee, Contributing Writer