A Prescription for Controversy: Antidepressants and Teen Suicide

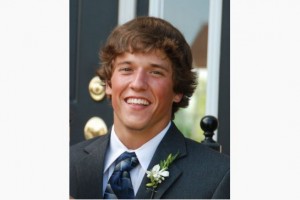

Brennan McCartney was described as fun-loving and good-natured by his friends and family. Known to wear his heart on his sleeve, Brennan came home in November of 2010 with Cipralex, an antidepressant, after visiting his doctor for a chest cold. His parents were astonished. He did not seem depressed.

Brennan took the medication for 4 days as prescribed, and on November 8th he left his home, drove to the store to purchase rope, and later that afternoon committed suicide.

Susan, a long-time friend of the family, tells the Trauma & Mental Health Report, “I grew up with Brennan, and when he died I really struggled to understand. There are comments on some [online] forums that he must have been depressed and that his parents just didn’t know. But he never was a boy who hid his emotions. From childhood, everyone around him knew whether Brennan was happy or sad. And after his death, a psychologist went through Brennan’s medical and school records and said that his family and friends did not miss anything, his record showed no red flags.”

Selective serotonin reputake inhibitors (SSRI), like the Cipralex Brennan took, work by blocking the re-absorption of serotonin in the brain. Often referred to as blockbuster drugs, SSRIs are among the most popular prescribed medicines in medical history.

Director Steven Soderburgh’s recent film, Side Effects, questions our complicated relationship with psychotropic drugs. After a young woman is prescribed an antidepressant, she has an unexpected bout of psychosis causing her life to unravel. The release of this movie has come in the wake of a heated debate regarding the over-prescription of antidepressant medication, especially for children and young adults, causing even more questions to be asked.

Last year, The Toronto Star highlighted Brennan’s case in an investigation on Health Canada’s refusal to look into individual reports of suspected side effects of certain psychotropic medications.

For years psychiatrists have known about something called “roll back.” Antidepressants sometimes have an activating effect that can give depressed patients the energy to follow through on suicidal impulses before their antidepressant treatment takes effect.

Further, CanWest News reports that some of Canada’s child psychiatrists worry antidepressants are being handed out far too easily. They say their soaring use reflects our growing intolerance for moodiness, shyness, anxiety, and other normal life problems.

What are the effects these medications have on people who are distressed to some extent, but not necessarily clinically depressed?

Susan tells us that Brennan was “down in the dumps” over a break-up, but not depressed. She goes on to say, “I think the way we define clinical depression should change, so that we cease using it to describe sadness.”

In an interview, Nancy McCartney, Brennan’s mother said, “Brennan was not depressed, he was sad, and tragically a drug he never needed in the first place caused fatal side effects.”

When did the naturally occurring emotions of sadness or anger become a psychological illness? Aggressive marketing by drug companies in the last few decades has transformed mild depression and even sadness into a disease of “serotonin deficiency,” influencing the administration of SSRI’s to teens.

A complicating factor is that when teenagers take antidepressants, they may not react the same way as adults do.

The Harvard Mental Health Letter notes that “Teen bodies do not absorb and eliminate drugs in the same way adult bodies do, and their brains may be affected differently as well. A child’s development could be detoured by a misapplication of drugs.”

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) information describes that individual response to these medications cannot be predicted with any certainty.

A 2003 study by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) found that no completed suicides occurred among nearly 2,200 children treated with SSRI medications. But about 4 percent of those taking SSRI medications experienced suicidal thinking and some suicide attempts, twice the rate of those taking placebo, or sugar pills.

As a result, the FDA issued a “black box” label warning, the most serious type of warning in prescription drug labeling, indicating that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behaviour.

Critics of the black box warning claim that the label scares people away from potentially helpful treatments. In a recent study appearing in the American Journal of Psychiatry, SSRI prescriptions for children and teens decreased by 22% in the U.S. in the year after the black box warnings were issued.

Some even argue that these efforts to save lives by curtailing purportedly harmful antidepressants have backfired. U.S. youth suicide rates increased by 14% between 2003 and 2004, possibly because patients are not receiving pharmacological treatment they need due to fear of the medications’ side effect. This is the largest year-to-year change in suicide rates since 1979 according to biostatistician Robert D. Gibbons and colleagues at the University of Illinois.

So the jury is still out. The link between SSRI prescriptions for teens and youth suicide seems tenuous at best.

Still, there is an important question at play here, one that relates directly to the development of our young people into adulthood, one that is at the heart of the Brennan McCartney case. That is, what do we expect normal to look like in our youth? Shouldn’t young people experience sadness? And what exactly do we want to be medicating away?

Sadness and depression are not synonymous. Our relationship with antidepressants is described aptly by author Robert Whittaker in his book, Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America.

“If you expand the boundaries of mental illness, which is clearly what has happened in this country during the past twenty-five years, and you treat the people so diagnosed with psychiatric medications, do you run the risk of turning an anger-ridden [or down in the dumps] teenager into a lifelong mental patient?”

We don’t know yet if antidepressants cause young people to take their own lives. But when we medicate away teen angst, grief and other normal -albeit uncomfortable- feelings, is there something else, something very precious that we take from them as well?

–Anjani Kapoor, Contributing Writer