Children Who Kill Are Often Victims Too

In 1993, in Merseyside, England, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson were charged with the abduction and murder of 2-year-old James Bulger. Bulger had been abducted from a shopping mall, repeatedly assaulted, and his body left to be run over by a train. Both Venables and Thompson were 10 years old at the time.

The public and the media called for justice, seeking harsh punishment and life imprisonment for the murder of a child. The boys were labeled as inherently evil and unrepentant for their crimes.

When there are crimes against children, it is common for the public to view the victims as innocent and the perpetrators as depraved monsters. But what do we do when the accused are also children?

Instances of children (12 years of age and younger) who have killed other children are extremely rare. In a study conducted by University of New Hampshire professors David Finkelhor and Richard Ormrod for the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), murders of children committed by those aged 11 and under accounted for less than 2% of all child murders in the U.S. Cases also tend to differ significantly, so conclusions can be difficult to make. But there are some similarities that have emerged, telling us about the minds of child murderers.

Children who murder have often been severely abused or neglected and have experienced a tumultuous home life. Psychologist Terry M. Levy, a proponent of corrective attachment therapy at the Evergreen Psychotherapy Centre, notes that children who have severe attachment problems (which often result from unreliable and ineffective caregiving) and a history of abuse may develop very aggressive behaviours. They can also have trouble controlling emotions, which can lead to impulsive, violent outbursts directed at themselves or others.

Other similarities among child murderers include having a family member with a criminal record, suffering from a traumatic loss, a history of disruptive behaviour, witnessing or experiencing violence, and being rejected or abandoned by a parent. Problems in the home can be particularly influential. If a child witnesses or experiences violence, they are likely to repeat violence in other situations.

What a child understands at the time of the crime is of great importance to the justice system. The minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) is the age at which children are deemed capable of committing a crime. The MACR differs between jurisdictions, but allows any person at or above the set chronological age to be criminally charged, and receive criminal penalties, which can include life imprisonment.

Many courts consider criminal responsibility in terms of understanding. So they may consider someone criminally responsible if, at the time of the crime, they understood the act was wrong, understood the difference between right and wrong or understood that their behaviour was a crime. But this approach has been criticized as being too simplistic. Criminal responsibility requires the understanding of various other factors, many of which children cannot appreciate.

Children may know that certain behaviours are ‘wrong’, but only as a result of what adults have taught them, and not because they fully understand the moral argument behind it. Morality and the finality of death are abstract concepts, and according to theorists such as Swiss psychologist-philosopher Jean Piaget (whose theory of child development has seen much empirical support), most children under 12 are only able to reason and solve problems using ideas that can be represented concretely. It is not until puberty that the ability to reason with abstract concepts (like thinking about hypothetical situations) develops.

Prepubescent children are also not fully emotionally developed, and less able to use self-control and appreciate the consequences of their actions. This, in combination with the fact that many child murderers are impulsive, aggressive, and unable to deal with their emotions, suggests that when children kill, they are treating their victim as a target, as an outlet for violence. Most victims are either much younger than or close to the same age as the perpetrators, which may suggest they were chosen because they could be overpowered easily.

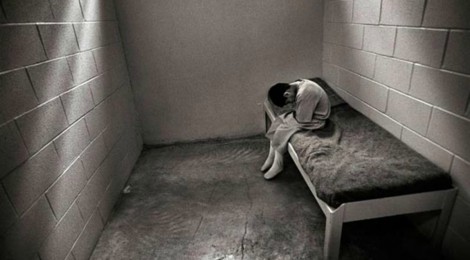

Research to date suggests that child murderers don’t fully understand the severity or implications of their crimes. And psychiatric assessments have shown intense psychological disturbance, making true appreciation of the crime even less likely. Yet many children have been found criminally responsible and sentenced in adult courts.

Jon Venables, Robert Thompson, and Mary Bell received therapeutic intervention while incarcerated, and have since been released. As far as the public knows, only Venables has reoffended. However, Eric Smith (convicted of killing 4-year-old Derrick Robie) remains behind bars today, even though he was imprisoned at 13.

Critics of judicial leniency for children accused of murder often cite the refrain ”adult crime; adult time,” choosing to focus on the severity of the crime rather than the age and competency of the offender. Make no mistake; the murders of these children were brutal, depraved acts that caused intense suffering for the victims, their families, and communities.

But in our zeal, in our outrage, do we dehumanize these children? Children who -like their victims- can be victims too.

-Jennifer Parlee, Contributing Writer

Of course…..and what’s shocking and appalling is how many adults just don’t want to know…..locally we had a teen “shooter” whose background would make any grown man with a heart cry…..and his background got published! But many adults are so ignorant of child development that they could not process what they read in a manner which enabled them to understand how many lapses in this boy’s home and family situation and also within the school system were in play which turned this teen into a “shooter.” He was torn to shreds in the papers and only the 4 kids he killed got sympathy.