Psychological Trauma and the Brain: Interview with Kim Shilson

Neuroscientists over the last few decades have discovered how trauma and fear affect the brain, especially the impact of experiences on child neurodevelopment. The brain adjusts to patterned-repetitive experiences that are understood through our senses. Nurturing environments result in healthy growth, while traumatic experiences result in unhealthy neurodevelopment.

The Trauma and Attachment Report had the opportunity to interview Psychological Associate Kimberley Shilson, author of Benjee and His Brain, to learn how traumatic experiences have a physiological effect on brain development.

Q: How is the brain affected by psychologically traumatic life events, and how is it affected long-term?

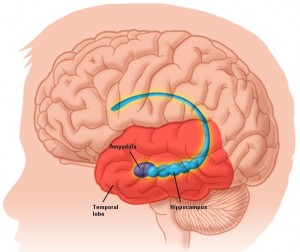

A: Research is increasingly showing that psychological trauma impacts such brain areas as the amygdala (involved in emotion management), and the hippocampus (involved in memory and memory consolidation). If trauma occurs repeatedly or over a prolonged period, cortisol (a hormone released during times of stress) is released too much, subsequently activating the amygdala and causing even more cortisol to be released. It is a self-perpetuating cycle that leaves the individual with heightened sympathetic arousal (“fight” or “flight” response). Research has shown that the hippocampus shrinks in volume in individuals with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which can have negative effects on memory.

Q: What are the effects of the change in the brain in terms of behaviour and functioning?

A: The amygdala acts like a switching system, sending incoming information from our environment to the cortex of our brain. Here the information is processed and made sense of, allowing us to address and process life events, for example, “Is this situation safe or dangerous?” The amygdala of traumatized individuals is often overly sensitive, resulting in extreme alertness. These individuals may appear aggressive, as they might be overly sensitive to perceived threats (words or gestures from peers), or withdrawn due to fear of being close to others.

The hippocampus plays a role from early life with storing memories in our brain, thus is important in a child’s learning process. Traumatized individuals may be adversely affected by negative memories, which can result in difficulty in learning. Their concentration may be impacted by intrusive images/memories during the day and nightmares affecting their sleep during the night.

Q: How do these behaviours translate into problematic adult functioning?

A: Adults traumatized as children, whether through physical/sexual abuse or profound neglect, may have challenges with forming and maintaining relationships because of negatively affected brain areas. They may develop inappropriate ways to deal with people in their lives, for example, they may have difficulty expressing their emotional needs and often remain distrustful of others.

Abused as children, adults who lack a secure attachment may become avoidant of establishing relationships, or overly dependent on others to meet their needs. In addition, they may turn to unhealthy coping strategies such as substance abuse, self-injurious behaviour, or eating disorders in efforts to manage their distress. Diagnoses such as depression, bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder (among others) are often seen among trauma survivors.

Q: Will a person who experiences multiple traumatic events be affected differently than the individual who experiences only a single trauma?

A: A single traumatic event may not have as great an impact as repeated exposure or severe neglect. The period between 0-36 months is considered crucial for maximizing brain development. For instance, the communication of information between the different brain areas is crucial for functions such as memory development.

The developing brain is experience-driven such that we learn through our experiences, especially in children. These experiences are programmed as memories in the brain, so repeated experiences become “hard-wired.”

Q: What are some of the neurological differences seen between children who experience trauma at a young age and adults who experience trauma in adulthood?

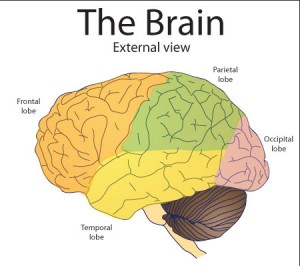

A: Children’s frontal lobes (involved in meaning-making) are not fully developed, since this occurs in later adolescence. Children exposed repeatedly to traumatic events do not have the capacity to process experiences in a sophisticated way. Beliefs such as “the world is not safe” are developed in the child’s brain and they may act unconsciously in ways that confirm those core beliefs.

Adults with their fully developed brains however, may be able to place a traumatic event in the context of many life experiences. Adults may require less intensive treatment following a traumatic experience due to their increased capacity for meaning-making.

Q: Can you describe the connection between neuroplasticity and the effects of traumatic events?

A: Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganize itself through new connections and brain growth. Awareness of this potential provides a sense of hope to individuals suffering from post-traumatic sequelae as well as their treatment providers. Treatment that considers the brain’s neuroplasticity can, in a sense, reverse the effects of trauma. A great book on neuroplasticity is: The Brain That Changes Itself, by Norman Doidge.

Q: In what ways do you tailor your treatment of trauma to account for the developing brain of children?

A: Traumatized children can present in a variety of ways such as the child being overly alert, impulsive, distractible, hyperactive and/or emotionally labile. Their extremes in behaviour can be confusing to them and to their caregivers, and they may have received diagnoses such as attention deficit disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or bipolar disorder.

Treatment focuses on helping children learn to regulate their emotions or calm themselves when distressed, and to recognize when they are distressed, by increasing awareness of physiological responses. Caregivers are usually involved in treatment, since the parent-child attachment has frequently been compromised in traumatized children.

Treatment may involve working with caregivers to become more attuned to their children and learn ways to interactively regulate their child’s behaviour. It is important to note that caregivers sometimes require treatment themselves in order to effectively work with their children.

Q: How does treatment itself affect the brain?

A: Repeated new experiences can, in a sense, rewire the brain, given the brain’s natural neuroplasticity. These new experiences can facilitate reorganization of the brain. Models such as Sensorimotor Psychotherapy work from a bottom-up approach, meaning the focus is first placed on increasing awareness of physiological sensations.

Trevor Green, a Canadian soldier hit in the head with an axe while in Afghanistan, has shown the potential for the brain to reorganize and regenerate itself. His brain was nearly split in half but after 6 years of surgery and therapy, Trevor has learned to talk, move, laugh and smile again. In addition to his physical incapacitation, Trevor had PTSD, depression and feelings of hopelessness. His story is a testament to the incredible capacity of the brain to rewire after trauma. Trevor’s story has been documented by W5, a Canadian news show, in a video entitled “Baby Steps.”

To learn more about Kim and the neuroscience behind trauma visit: http://www.insideoutpsych.ca/

-Saqina Abedi, Contributing Writer