U.S. Gun Laws Mistakenly Target the Mentally Ill

In the wake of public tragedy, there is widespread demand for change. Generalized, sweeping measures are often put in place as a quick response to prevent a given disaster from repeating. But while swift changes may appease public outrage, they are often ineffective.

U.S. gun control legislation, with its focus on mental illness as the problem has not worked in the past, and there is no reason to think it will work now.

In 1968, the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. led to public outrage. Lawmakers responded with the Gun Control Act. It forbade people with known substance addictions, a criminal record or those “adjudicated as a mental defective” (a term still present in U.S. law today despite the pejorative wording) from legally buying or possessing firearms. To be deemed “mentally defective” by the court, individuals must have “marked subnormal intelligence or mental illness, incompetency, condition or disease” and be “a danger to themselves or others.”

In theory the new Gun Control Act appeared to be the answer, but it was created before computer databases -or computers as we know them- existed. There was no easy way to form a comprehensive list of those banned from owning guns.

The Brady Act, enacted in 1993 after the shooting of Ronald Reagan and his press secretary James Brady, sought to change that. Part of the bill called for the formation of the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), a digital system that would allow licensed firearms dealers to instantly confirm that their customer was not barred from buying a gun under the Gun Control Act.

But the system was far from flawless. In 2007, 14 years after the Brady Act came into effect, the Virginia Tech massacre in Blacksburg Virginia left 32 dead and 17 wounded. The gunman, Seung-hui Choi, had a documented history of mental illness, including a 2005 temporary detainment in a behavioural health unit after being deemed “an imminent danger to himself or others,” yet he had acquired the gun used in the shooting legally.

According to legal criteria, Choi should have been in the NICS database, but he wasn’t. What went wrong?

Following the shooting, the F.B.I. released a statement that only 22 of the 50 states were submitting mental health records to the NICS. Virginia was one of those 22 states, and was in fact the leading nation in reporting. But in Virginia, the form to report someone to the NICS database asks if they have been committed to a hospital or found to be mentally incapacitated by a judge. Since Choi’s detainment led to treatment as an outpatient, he was never committed, and so he escaped the list.

The NICS Improvement Amendments Act (NIAA) of 2007 followed soon after. It offered monetary grants to encourage states to improve their records systems and forward their information, and included penalties on other existing grants if they failed to comply.

Despite these efforts, in the four years before this change there were eight mass shootings, while in the four years following, there were 19. The measures were not working. Why?

The Gun Control Act, the Brady Act, the NIAA were each put into place after a tragic public incident, and each was designed the same way: to allow the majority to continue to purchase arms, while placing more restrictions or denials on those the state has deemed dangerous.

This approach is ineffective. Gun control laws mistakenly target the mentally ill. The focus has been to prevent people who the media often portrays as dangerous and unpredictable from purchasing firearms. However, as of 2010, mental illness accounted for only 0.7% of the successful denials of firearm purchases. Only one in ten gun related homicides are estimated to involve mental illness.

The bottom line: Mental illness is not the main problem as far as gun-related homicides are concerned, and efforts to curtail gun-related deaths based on mental illness are not successful.

Internationally, different approaches that do not target the mentally ill have been more effective. After a tragic shooting in 1996 in Port Arthur, Australia, gun laws were tightened to reduce the number of guns including bans on assault weapons, semi-automatic and pump-action shotguns, and tighter restrictions on handguns. The government even purchased 631,000 guns from owners and destroyed them. The evidence shows that such measures are effective.

Researcher Olav Niellsen, of the University of Sydney explains, “…there were 13 mass shootings with 112 fatalities in the 15 years before 1996, and there have been none in the 15 years since. We estimate that the change in firearms laws in Australia in 1996 has already saved about 2,000 lives.”

Currently there are 9 guns for every 10 people in the United States and as the guns keep piling up, so do violent gun-related deaths.

On December 14th 2012, Adam Lanza shot his mother, and then opened fire at Sandy Hook Elementary school in Newtown Connecticut, killing 20 children, one of the worst gun-related violent crimes in U.S. history. Although he is alleged to have suffered from Asperger’s and behavioural problems, no records exist of him being found by “a court, board, commission, or other lawful authority” to be a “mental defective” and he was not on the NICS. Further, the two pistols and assault rifle he used were purchased legally by his mother.

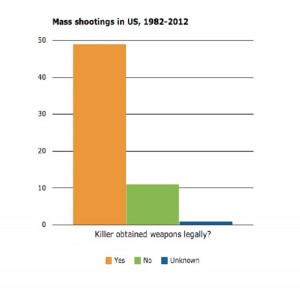

As it turns out, most guns in mass shootings are purchased legally by someone other than the shooter.

This shooting has resulted in a call for change that law makers are once again answering. On Wednesday January 16th 2013, President Obama called for changes to gun legislation as well as $500 million in spending to deal with what he calls “an epidemic of violence.”

Will this proposal be the silver bullet that stops such shootings? Only time will tell if lawmakers get it right this time. So far, the measures put into place, such as the Brady Act and the NIAA haven’t cut it. Something new needs to be done, and done right this time, an approach that does not target the mentally ill.

The opportunity to change how a nation handles guns comes along rarely. The price of getting it wrong means the further loss of innocent lives.

-Bradley Kushnier, Contributing Writer