Rape Chants Prevalent on University Campuses

“Y-O-U-N-G, we like ’em young, Y is for your sister, O is for oh so tight, U is for underage, N is for no consent, G is for go to jail.”

Frosh week: When nerves and expectations are high, and when first-year students are eager to meet new friends.

In September of 2013, university officials were outraged that some University of British Columbia (UBC) and St. Mary’s University (SMU) students glorified sexual assault by chanting a rape song during frosh week.

Chanting at frosh events is supposed to facilitate school-pride and community. Returning students organize frosh events to represent their schools with dignity. But like every year at UBC and SMU, frosh leaders continue to endorse sexist chants. The president of student council at St. Mary’s, who since resigned, said, “I never thought anything about it” since he heard the chant four years earlier.

So do students who voluntarily take part in a rape chant actually endorse it?

The desire to be part of a group can mean surrendering individuality. Social psychologists call this phenomenon deindividuation and it explains why rational individuals can become unruly in crowds. While group chanting is used as a social bonding technique during frosh –where fitting in and making friends is a priority– chanters may not realize they are legitimizing rape.

Historically, rape chanting has been associated with acceptance of violence against women says Otutubikey Izugbara, professor of medical anthropology at the University of Oyo, Nigeria. What’s concerning is that university campuses are unknowingly endorsing this mentality when young women ages 16 to 24 are four times more likely to be assaulted sexually than any other age group.

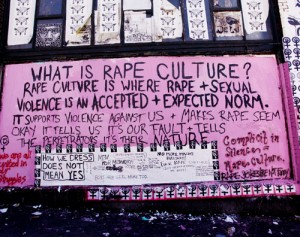

Political science professor Janni Aragon of The University of Victoria was not surprised by the frosh chants. “We live in a hyper-sexualized world where social justice activists, rape crisis workers, and academics working in women’s studies or other fields continually explain that rape culture thrives.” She explains that an atmosphere of rape culture can turn a rape chant into a “light-hearted moment,” one that underplays the severity of the ritual.

Both UBC and SMU administrators promised sensitivity training, counseling, and anti-rape education for students. Among them, Robert Helsley, dean of the UBC business school voiced concern for student safety and communicated his assurance that such inappropriate events would no longer occur. St. Mary’s appointed a panel to recommend sexual violence prevention on campus, including former politician Laurel Broten, who drafted Ontario’s sexual violence plan.

Education is part of the solution. Jessica Carlson, a psychology professor at Western New England College and Danielle Currier, a sociology and women’s studies professor at the College of William and Mary reported that students who participated in a rape education course were found to have changed attitudes about rape. Students were more likely to see rape as a negative event rather than a neutral or positive one.

But when Helen Lenskyj, professor of social justice at The University of Toronto showed that 60% of Canadian college-aged males would commit sexual assault if they knew they would not get caught, are preventive programs being introduced too late?

In 2004, the Rand Corporation and Break the Cycle non-profit think tanks, questioned whether violence education programs are appropriately timed for university students. Their research shows that first sexual experiences often occur at a younger age, many of which are forced. High-school students are considered a high-risk group for unwanted sexual encounters.

Since then, rape education grants have increased for middle schools and high schools. Poco Smith, a professor of social work at Wayne State University and Sarah Welchans, a statistician from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics studied rape education in high-school students. They found that using an education peer group to explain male responsibility in sexual assault (as opposed to victim blaming) led high-school students to perceive rape as an objectively harmful event.

Still, it is challenging to reach younger students because parental consent is often a requirement, and there are few knowledgeable counselors to teach abuse prevention. Sexual education in general also tends to focus on heterosexual abuse, labeling the male as the abuser and the female as the victim. There is considerably less research that focuses on abuse in sexually diverse groups.

For victims of sexual assault, there is a social and psychological cost. Male-privileging rape songs can isolate victims, and encourages a celebration of trauma.

When two different universities bordering Canada are singing the same song at frosh week, you might wonder if other universities across Canada are doing it too.

Universities worldwide ought to pay close attention. When I was in high school, I didn’t wonder whether the chant I participated in was wrong. My guess is there are a whole lot of unaware students out there.

-Shira Yufe, Contributing Writer