Anorexia Affects Men More Than Previously Thought

Zachary Haines was 16 years old when a physical examination put his 5’7”, 230-pound body within the obese range. Soon after, Zachary began working out and watching his diet, entering his junior year at high school 45 pounds lighter.

But what started as a healthy lifestyle soon spiralled into a struggle with anorexia nervosa, an eating disorder characterized by severely restricting food intake. Like many other men and boys, Zachary’s extreme weight loss was not identified as an illness. In fact, it was ignored until he was hospitalized for malnutrition. Despite having many of the telltale signs of anorexia, Zachary’s condition went untreated.

Anorexia and bulimia are traditionally seen as “female problems.” But, recent studies show that approximately one third of people with anorexia and about one half of those with bulimia are men.

One of the influences thought to impact these men are the shifting ideals in the media that are putting pressure on men to become thinner.

While there may not be a direct causal relationship between media portrayals of the ‘ideal’ man and the development of eating disorders, these depictions contribute to a cultural context that glorifies their apparent normalcy. They may also influence males’ fears of becoming overweight, as male models face pressure to slim down and appear androgynous.

The thin ideal male image is also making its way into fashion.

In 1967, an average mannequin’s dimensions were a 42-inch chest and a 33-inch waist. Today’s average dimensions are a 35-inch chest and a 27-inch waist. With the average American man’s waist size being 39.7 inches, these changes represent a remarkably unrealistic objective.

For Zachary, fitting into smaller sized clothing after weight loss was a source of pride.

But during treatment this once enjoyable activity became emotionally painful: In Zachary’s words, “The most anxiety-inducing part for me is trying on clothes. If I go up a size, I think I’m going to be 230 pounds again.”

The signs that something was wrong were all there.

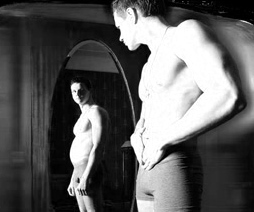

Despite working out for three hours per day while only consuming 1,400 calories, Zachary was continuously trying to lose more weight. By relying on inaccurate results from the Body Mass Index (BMI), doctors missed his emaciation. He had never fallen into the anorexic range because the BMI does not take into account the proportion of muscle to fat, even though his emaciation would have been evident if he were seen shirtless.

The growing number of stories like Zach’s has led to significant changes to how anorexia nervosa is diagnosed.

In the DSM-V (the most recent version of American psychiatry’s diagnostic manual), this change involved eliminating Criterion D, or amenorrhea (the absence of menstruation) to make the diagnosis gender-neutral.

Zachary recovered because he had support from his family and friends, private insurance, and access to physicians and psychiatrists, who he worked with closely.

To help his recovery, he had to change his wish to pursue becoming an athletic trainer to that of going into advertising.

Those without resources can also identify some of the signs of an eating disorder: extreme exercise behaviors, compulsive thoughts of losing weight, constantly feeling cold, and extreme food restriction.

These signs don’t discriminate between men and women, neither should we.

-Danielle Tremblay, Contributing Writer