Trauma and the Humanitarian Aid Worker

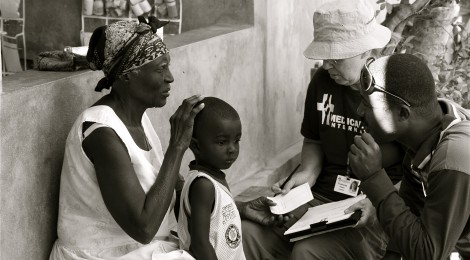

With rising political, economic and environmental instability, a growing number of the world’s citizens are becoming increasingly dependent on international humanitarian organizations for survival. It is estimated that there are well over 200,000 paid humanitarian aid workers, along with thousands of volunteers, providing aid across the globe in the form of poverty and disaster relief operations. These people live and work in some of the most hostile and dangerous regions. And that comes at a very high cost to the aid worker’s physical and psychological well-being.

Working long hours in high-risk conditions, they make decisions in life-and-death situations that affect many. Struggling with a demand for aid supplies greater than the resources available, aid workers often face great moral challenges that elicit high levels of stress.

I recently interviewed Olivia Westguard, a former humanitarian worker, about her work inCentral America after Hurricane Mitch:

When you are surrounded by mass suffering and chaos, it’s hard to know where to start. There were so many people in such rough shape. They would walk for miles, carry each other, camp outside our clinics. The lines were never-ending. Doing triage, it was up to me to figure out who was in the worst shape and who could wait. At times I felt like I was playing God. I had to pick the life-threatening cases first and just leave the rest. I felt pretty sick about it sometimes, especially when we had to stop and there were still people waiting. We could never do enough. It was overwhelming. We were already working 18 hours some days.

Studies have found that around 80% of aid workers experience distress symptoms, and that 3-7% suffer to an extent that interferes with their duties. Furthermore, exposure to this kind of environment comes with security risks.

Aid workers operate in violent and volatile regions, vulnerable to personal assault and kidnapping. Recently, there has been a surge in news stories covering violence towards humanitarian workers in the Horn of Africa,Sudan,Libya, andEgypt. In 2011, The Aid Worker Security Database reported over 500 aid workers were murdered, wounded or kidnapped while in the field during that year. For those surviving such encounters, traumatic effects can last for years. Olivia Westguard recalls:

Early one morning another doctor and I were setting up the pharmacy and preparing for the day. I was digging through a box in the backroom when I felt a hard object pressed against the back of my head and heard the words “Abajo!” (“Down” in Spanish). I looked over and saw the doctor being pushed into the backroom by a man. He had a gun to her head. When I went down on my knees I caught a flash of myself in a side mirror. The hard object pressed into the back of my head was an AK-47 held by a very large man. My head was spinning. I couldn’t breathe. I got on the floor, put my hands behind my head and prayed to anything and everything. That moment still stays with me. That feeling of helplessness, terror, and feminine vulnerability. Not knowing what was next. We were physically fine in the end. They robbed our medical supplies and shook us up. But, for a long time afterwards, even after I returned home, I would have moments where I would be right back there, shaking and terrified. I would see their faces. I could smell them. I ‘d see that mirror image over and over again and hear the doctor cry. I had horrible nightmares. I never realized it was post-traumatic stress. Besides the debriefing, no-one ever talked to me about it.

While many organizations train staff in debriefing procedures following a critical incident, there is controversy regarding the procedures’ effectiveness. The methods involve an evaluation of the event, addressing immediate thoughts, emotions and coping strategies. There are some critics who believe the debriefing process may be harmful to victimized aid workers and cause re-traumatization.

Extensive exposure to communal trauma, and at times personal trauma, can have a long-term impact on the mental health of humanitarian aid workers and result in a variety of issues such as post-traumatic reactions, feelings of hopelessness, depersonalization, detachment and burnout. Most humanitarian organizations’ mental health resources focus on preparing aid workers for difficult situations in the hopes of developing greater psychological resilience in the event of a crisis. But as Westguard explains:

There is nothing that can prepare you for the moment you have a gun to your head or the days and weeks after. There is nothing that can prepare you for how it will feel to have a child die in your arms, to see people living and dying in misery, to see bodies lining the streets, to hear thousands beg for help and not have enough for everyone. There is no information session or manual that can tell you how that will feel or when or how it will hit you. The debriefing sessions aren’t enough a lot of the time and we [aid workers] end up just trying to talk it out with each other but we aren’t qualified therapists, we just do what we can to support each other when it feels like too much.

The sharing of traumatic experiences has evolved into a group coping mechanism. In an industry offering very little formal psychological debriefing relative to the amount of traumatic exposure, it has become a way of coming to terms with the dangers of the business. This kind of social support has been identified as a critical buffer in the experience of trauma and is a vital asset to the promotion of aid workers’ psychological functioning.

Blogging has also become a great resource for humanitarian workers, and in recent years numerous blogs have featured independent aid workers and staff from various organizations. This has become an opportunity for isolated or distressed workers to share their innermost thoughts, feelings, and reflections on their daily experiences in the field and engage in a form of personal, self-guided debriefing. And, casual websites such as “Stuff Aid Workers Like…” feature humorous quips and jokes and focus on encouraging a light-hearted communal laugh at the challenges of the humanitarian business.

Unfortunately, despite the community’s growing online support network, in the real world very little personal psychological treatment and care for aid workers exists, especially when they are not working.

On returning home, many aid workers find themselves completely on their own, abandoned by the organizations they serve, left to process their experiences and feelings with little or no support. Over 70% of aid workers consider the debriefing and support that they received on their return home to be insufficient. And, many experience long term effects such as sleep disturbances, appetite changes, emotional shifts, and depression. With such a high rate of distress among staff, it has become apparent that organizations must start stepping up and expanding their psychological resources and services.

Many have called for mental health interventions to be implemented by aid organizations to address the growing concern over psychological well-being among aid workers. Some studies recommend that training programs be more extensive and assist aid workers in stress management activities and in early identification of distress. And, that they should foster the development of greater emotionally protective qualities such as emotional boundaries, positive framing, and compassion satisfaction – deriving a sense of pleasure and reward from the positive aspects of the job. Aid workers’ repeated exposure to traumatic or high-stress postings without breaks and proper debriefing should be prevented.

Without psychological support how can humanitarian workers continue their work in good health?

This vital human resource is of little use if its members are unable to heal, thrive and be productive. We must remember to care not only for the vulnerable, but also for those who are doing the work.

-Adriana Wilson, Contributing Writer