Using Art to Heal from Sexual Assault

Frizz Kid (Hana Shafi), a writer and visual artist based in Toronto, Canada, deals with themes of feminism, sexual violence, and self-care. Shafi first came to prominence through social media after the high-profile Jian Ghomeshi sexual assault trial in Toronto. Prominent radio personality Ghomeshi was charged with, but subsequently acquitted of, multiple counts of sexual violence.

Ghomeshi’s victims were essentially blamed for the assaults, and their stories were discounted as inconsistent or false. Following the trial, numerous artists and activists joined together under the hashtag #WeBelieveSurvivors—Shafi among them. And her craft was deeply affected and altered by the outcome of the trial.

In an interview with the Trauma and Mental Health Report, Shafi discussed the impact on her art:

“The period after the trial was really difficult. The constant media coverage of what happened to these women and the ultimate lack of justice was hurtful, particularly to survivors of sexual assault. A compassionate perspective was missing. The trial turned into an attack on their characters instead of focusing on the wrong that was done to them.”

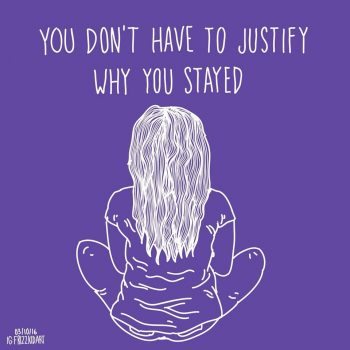

In reaction, Shafi began her most well-known work: her Positive Affirmation Series. Shafi combined drawn images with words to assert comforting phrases, such as “healing is not linear,” “it’s natural to have emotional baggage,” and “you are worthy of love.”

According to Shafi:

“The series has been a way for me to express solidarity with victims of sexual assault. I never expected the art to get as big a reception as it has.”

Her art serves several purposes. She creates it to cope, as well as to help others:

“All my pieces have a purpose for me as much as for others. I find it personally healing to create, but I also want to help others and create a community of people around art where we can heal together, be angry together, be sad together, and create together.”

To engage more closely with her audience, Shafi recently collaborated with Ryerson University as their artist-in-residence. There, she conducted free workshops on making zines, which are short, self-published magazines made by photocopying and binding artwork, poetry, or other writing.

Participants were invited to answer the following:

“Have you ever thought about what you would say to the person who sexually assaulted you? What would you want your peers to know? What would you like to remind yourself?”

These works were compiled for an art installation, titled “Lost Words.” In an Instagram post, Shafi explained:

“Through these questions, we can communicate the lost words; all the things that have been left unsaid but need to be heard.”

When speaking with the Trauma and Mental Health Report, she added:

“I really wanted there to be a platform for people impacted by sexual violence to speak about their experiences. To say the things they never had an opportunity to say, or felt they couldn’t say. I wanted people to get the sense that they could say whatever they wanted in that space and that they would be safe doing so. This is them talking back. I think having an outlet like this is critical for the healing process.”

Shafi also stressed the important role that participant anonymity played in “Lost Words:”

“There’s safety in anonymity. People are not super understanding about this subject matter; there needs to be anonymity.”

Some may be familiar with the therapeutic practice of writing a letter to a person who has hurt them, then destroying the letter. These so-called “hot letters” are used as a form of emotional catharsis.

Similar ideas were explored by Shafi in this exhibit. “Lost Words,” however, dealt with having private and painful thoughts read by the public. These works were exhibited in conjunction with the Sexual Assault Roadshow, a travelling art gallery that aims to change the public’s perception of survivors of sexual assault. This decision to exhibit to the general public was tactical. Shafi explained:

“I think through viewing the works, they begin to understand; they get a small glimpse into the reality of a survivor; they see the injustice, trauma, and frustration.”

Survivors of sexual assault benefit from the exhibit too, Shafi argued:

“They express what they’ve always wanted to say but never had the platform for. It may have been unsafe for them to say things before, but they are now excited that their work will be seen—that they can speak in a public setting while remaining anonymous.”

The reception to the exhibit was overwhelmingly positive, with many reaching out to Shafi to express their gratitude. Others, Shafi said, were genuinely surprised by the exhibit, which she suspected was a reality check for them.

Shafi stressed that she is not giving survivors a voice because they have their own voice.

“I think what I’m doing is giving them a space to feel heard and validated. Giving them art that emphasizes their experience, highlights their issues, and provides a compassionate space.”

– Fernanda de la Mora, Contributing Writer