Virginity Tests Place Physicians in Quandary

In October of 2013, the College of Physicians in Quebec, Canada, ordered doctors to stop performing virginity tests on women.

Remarkably, it took a formal directive from a governing agency to stop the degrading practice. Over the 18 months preceding the announcement, there were five reports in Quebec alone of requests for virginity tests. But physicians note that the tests are actually a hidden taboo practice occurring at a very high frequency.

Requests are often made by a woman’s family, seeking to fulfil traditional requirements of providing proof of ‘innocence’ for marriage. Physicians are actively pressured by families to conduct these tests and sign certificates for review by both families, putting doctors in a moral quandary: refusing to perform the test or giving a negative result can dishonour a woman in the eyes of her family, but going along with the procedure represents collusion.

Practiced all over the world, virginity tests are a longstanding tradition. Many African nations uphold the custom, purportedly as a means of controlling AIDS by checking which women are ‘safe’ to marry. But tests do not definitively determine the presence of HIV or AIDS as it is possible for people to become infected through other means – sharing needles or from parents.

And the test is highly subjective. In addition to many women being born with negligible hymens, stressful activities and even tampons can lead to ‘loss of virginity’. Other versions of the test, such as checking for overall laxity of the vagina, are painful and embarrassing.

In 2011, women attending protests in Egypt were rounded up and subjected to virginity tests and other forms of sexual assault and humiliation by police and armed forces. In Indonesia, high-school officials are considering implementing virginity tests as a way of controlling student behaviour and encouraging chastity. In Iraq, virginity tests are regularly ordered by the courts, whereupon husbands can sue their wives and their families for damages and dissolution of marriage. And in India, not only is it common practice to put brides-to-be through the procedure, but even rape victims are subjected, which, if they fail, may mean shunning by families and others.

In Canada, requests for virginity tests have come from parents concerned about daughters’ choices, as well as from educated professionals afraid of disappointing husbands-to-be. While it may seem a relief that the procedure now has been deemed outside the scope of physician practice, pressure remains in some communities, leading many physicians to give out fake ‘virginity certificates,’ to placate families and protect the privacy and dignity of the women in question.

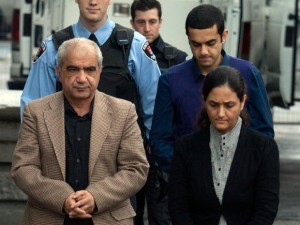

As witnessed by Canadians just over two years ago, traditions like these can escalate with tragic consequences. In June of 2009, Mohammad Shafia, reportedly incensed at his ex-wife’s and daughters’ behaviours, engaged the help of his new wife and son in brutally murdering the four women. Known as honour killing, this practice views women as male property. Similar beliefs hold female chastity and obedience in high regard, with violations of cultural norms being equated with treason, to be cleansed only through death.

In Montreal, Quebec, it was recently discovered that hymenoplasties – surgeries which artificially recreate the hymen so as to cause bleeding during intercourse – have become the second-most popular plastic surgery. Alarmingly, private medical organizations have stepped up and begun offering secret, cash-paid procedures for several thousand dollars to interested parties.

It is hard for physicians to agree on the moral dilemma of virginity testing. One televised discussion shows some doctors stressing the inaccuracy of virginity tests, and how the inherent pain and humiliation associated with them is enough to justify abolishing them entirely. In contrast, Rachel Ross, physician and sexologist, points out that virginity tests can be useful in criminal cases involving children to determine whether sexual abuse took place.

The biggest quandary facing physicians is whether to let virginity tests and hymenoplasties be available to the public. The reasoning behind both has been examined extensively by medical ethicist Marie-Eve Bouthillier, who explains that banning these procedures may seem like the best step to end these women’s pain and humiliation, but it may also subject them to violent retribution or even more demeaning tests conducted by family members or religious leaders.

Conversely, Bouthillier states that “sometimes the virginity certificate will be the ticket for a forced marriage,” meaning that physicians who perform the tests or even give false results may still be condemning these women to a life of suffering.

A difficult choice indeed. Right where the paths of medicine, ethics, and culture collide.

-Nick Zabara, Contributing Writer