Rape Victims’ Reactions Misunderstood by Law Enforcement

In 2008, 18-year-old Marie reported being raped at knifepoint in her apartment. Confronted by the police with allegations that she was lying, she conceded under pressure that the rape may have been a dream. Then, after being aggressively interrogated about her story, she finally admitted to making it up. She was subsequently charged with false reporting.

The report, however, was not false. In June 2012, Marc O’Leary pleaded guilty to 28 counts of rape and was sentenced to 327½ years in prison, including 28½ years for the rape of Marie.

Rape is unlike most other criminal offenses. The credibility of the victim is often on trial as much as the guilt of the assailant, despite the fact that false rape accusations are rare (only an estimated 2-8% of cases are fabricated).

Sergeant Gregg Rinta, a sex crimes supervisor at the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office in Washington, deemed that what happened to Marie was “nothing short of the victim being coerced into admitting that she had lied about the rape.” Rinta recounted in an external report of the department’s handling of the case how Marie was subjected to “bullying and hounding”, as well as threats of jail time and withdrawal of housing assistance.

Steve Rider, the commander of Marie’s criminal investigation, considers her case a failure. In an interview conducted by ProPublica and The Marshall Project, he explained:

“Knowing that she went through that brutal attack—and then we told her she lied? That’s awful. We all got into this job to help people, not to hurt them”

The seed of doubt was planted when the police received a phone call from Marie’s former foster mother Peggy and another foster mother, Shannon. One of their biggest issues was that Marie was calm while describing the attack, rather than upset. Shannon stated:

“She called and said, ‘I’ve been raped. there was just no emotion. It was like she was telling me that she’d made a sandwich.”

Peggy remembers:

“I felt like she was telling me the script of a Law & Order story. She seemed so detached and removed emotionally.”

Hearing these accounts from those closest to Marie led the police to distrust her story, and the situation unfolded from there. In rape cases, a judgment of legitimacy often focuses on the victim’s reaction during and following the event instead of on the assailant’s behaviour.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Rebecca Campbell spoke about the neurobiology of sexual assault in a talk to the National Institute of Justice. She explained that victims are flooded with high levels of opiates during a rape—chemicals in the body intended to block physical and emotional pain, but which can also dull the victims’ feelings:

“The affect that a victim might be communicating during the assault and afterward may be very flat, incredibly monotone—like seeing no emotional reaction, which can seem counterintuitive to both the victim and other people.”

This misperception contributes to sexual assault cases not going to trial. Of rape cases that are reported, 84% are never referred to prosecutors or charged; 7% are charged but later dropped; 7% get a plea bargain; 1% are acquitted; and only 1% are ever convicted.

Dr. Campbell identifies part of this problem as the police misunderstanding victims’ reactions as they recount their trauma. Based on this confusion, police officers make assumptions about the legitimacy of what they hear and often discourage victims from seeking justice. Officers may even secondarily victimize them.

Secondary victimization is defined by Dr. Campbell as “the attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of social system personnel that victims experience as victim blaming and insensitive. It exacerbates their trauma, and it makes them feel like what they’re experiencing is a second rape.”

On average, 90% of victims are subject to at least one secondary victimization in their first encounter with the justice system. Victimization includes discouraging victims from pursuing the case, telling them it’s not serious enough, and asking about their appearance or any actions that may have provoked the assault.

These incidents have a profound effect on victims, as conveyed by Dr. Campbell, with many reporting feeling depressed, blamed, and violated. In fact, 80% feel unwilling to seek further help. As a result, many rape victims withdraw their complaint. To make matters worse, only 68% of rape cases are reported in the first place.

Sharing information on the neurobiology of trauma could be a powerful tool in educating police officers who don’t understand victims’ reactions. Evidence of the neurobiological changes that lead to flat affect or what appear to be huge emotional swings after an assault may help police better serve this population.

Furthermore, normalizing a range of reactions from rape victims, rather than accepting preconceived notions, may lead to a safer and more effective environment for reporting sexual assault. Knowledge about trauma can also serve to inform public discourse about sexual assault, as well as help victims to see their own reactions with compassion.

– Caitlin McNair, Contributing Writer

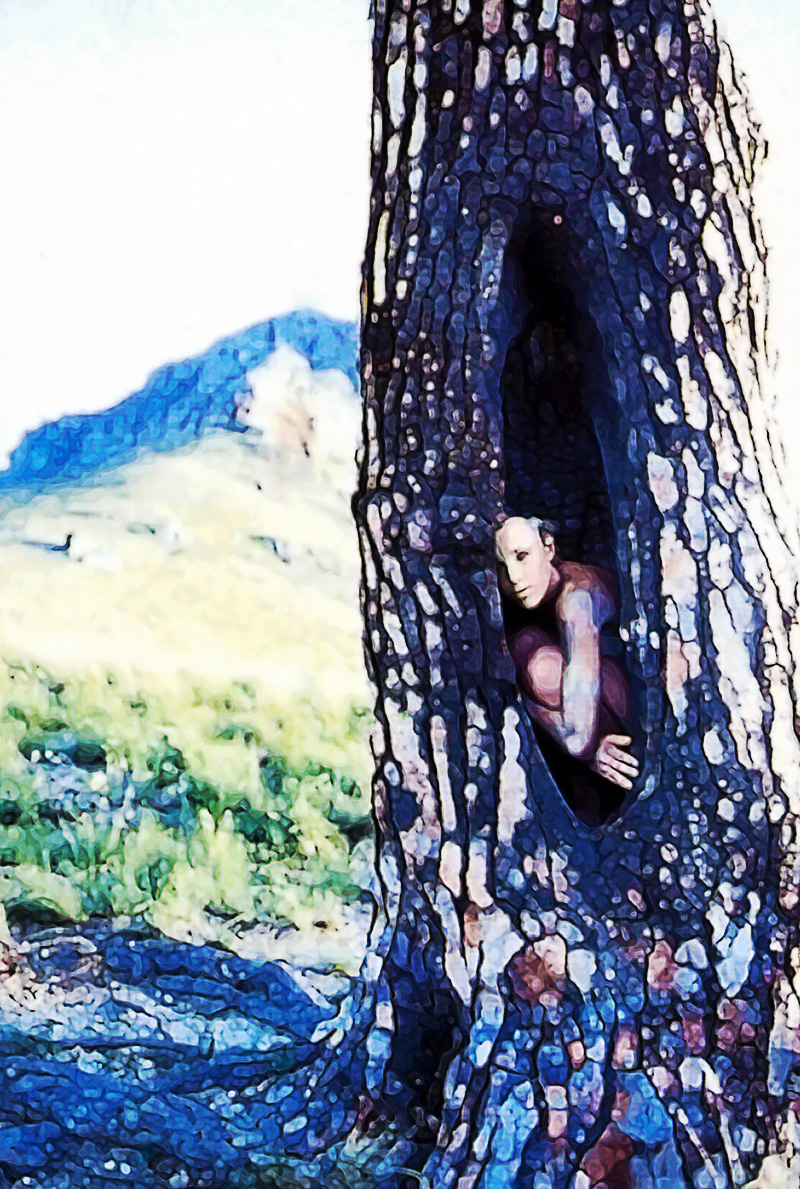

Image Credits

Feature: Richard George Davis, used with permision

First: Richard George Davis, used with permision

Second: Richard George Davis, used with permision

Well written and extremely informative. Secondary victimization is common and having these authority figures know about the reasoning for flat affect would hopefully allow for empathy rather than blaming the victim.

In my opinion, police need to add mental health and trauma training to their education. Every occupation does..

What we have is the law enforcement agency are themselves breaking the law, in failing to provide help and fair justice to these victims.