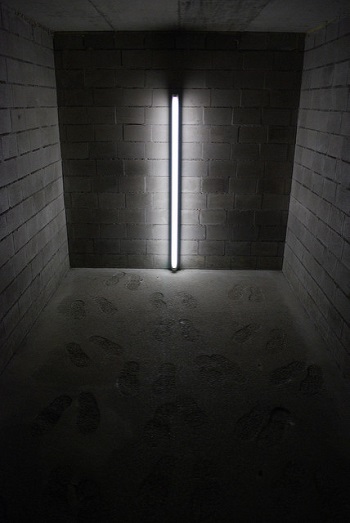

Solitary Confinement is State-Sanctioned Torture

Sixteen-year-old Kalief Browder spent three years in New York’s notorious Rikers prison, awaiting trial for robbery. Two of those years were spent in solitary confinement. Browder’s case was eventually dismissed and, after surviving four suicide attempts during incarceration, he was released. Suffering from depression and paranoia from his years in isolation, Browder died by suicide in June of 2015.

Former U.S. President Barack Obama referenced Browder’s story in an opinion piece he wrote for the Washington Post, explaining his decision to ban solitary confinement for juveniles in all federal prisons, and calling for greater restrictions on its use as a punitive measure. New York had already ended the use of isolation for prisoners 16 and 17 years old, but in October 2016, the age restriction was extended to age 21 and younger.

In 2015, Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau moved to ban the use of long-term solitary confinement by placing a 15 consecutive-day limit on its use—as of writing, this ban had not come into effect. His decision was motivated in part by the death of Ashley Smith, a young offender who had spent more than 1,000 days in isolation. At the age of 19, while being held in solitary, Smith died by hanging herself. A coroner’s inquest ruled her death a homicide, indicating that other people’s actions were factors in her death.

Reforms are moving in the right direction, but results of a 2011 United Nations (UN) report raise the question—should isolation be permitted under any circumstances? UN Special Rapporteur Juan E. Mendez said in this report:

“Solitary confinement, [as a punishment] cannot be justified for any reason, precisely because it imposes severe mental pain and suffering beyond any reasonable retribution for criminal behaviour and thus constitutes an act defined [as] … torture.”

Nevertheless, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, many American states impose no restrictions on the use of solitary confinement, even for juveniles. In Canada, there is currently no limit on how much time a prisoner can spend in solitary confinement. And, if adopted, the limits proposed by Trudeau will only affect federal prisons.

According to an American National Survey by the Association of State Correctional Administrators at Yale, “between 80,000 and 100,000 people were in isolation in prisons as of the fall of 2014.” In Canada, The Globe and Mail reports, “1,800 Canadian inmates are held in segregation on any given day.”

According to Mendez, the adverse health effects of this type of imprisonment are numerous, and include ‘prison psychosis,’ which can lead to anxiety, depression, irritability, cognitive disorders, hallucinations, paranoia, and self-inflicted injuries. Mendez concluded that “solitary confinement for more than 15 days…constitutes cruel and inhuman, or degrading treatment, or even torture”—well below the time Browder and Smith spent in isolation.

The adverse effects of solitary confinement on mental health have a long history of documentation. David H. Cloud, head of the Vera Institute of Justice’s Reform for Healthy Communities Initiative, stated:

“Nearly every scientific inquiry into the effects of solitary confinement over the past 150 years has concluded that subjecting an individual to more than 10 days of involuntary segregation results in a distinct set of emotional, cognitive, social, and physical pathologies.”

These findings prompted Kenneth Appelbaum from the Center for Health Policy and Research at the University of Massachusetts Medical School to write an article calling for American psychiatry to join the fight against the use of solitary confinement.

Many prison administrators disagree. In an interview with the Boston Globe, the Massachusetts Commissioner of Correction defended the use of solitary, explaining:

“We have to be realistic when we’re running these prisons. Segregation is a necessary tool in a prison environment.”

An article by Corrections One, an online news outlet for the correctional field, explains that segregation keeps jails safer by removing violent and dangerous inmates from the prison population, in the same way that imprisonment removes dangerous people from society. Segregation, the article states, is primarily used on prisoners that pose a risk of harm to themselves or others.

Speaking with the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC), Lisa Kerr, law professor at Queen’s University in Southern Ontario, reported that:

“Prison administrators have long been convinced that they cannot manage their institutions without easy, limitless recourse to segregation.”

Watch-dog groups point out that other countries apply the use of solitary confinement more selectively and with greater oversight than is used in North American prisons. In the U.K., while solitary is still in practice, the number of prisoners subjected to this form of punishment is much lower. Even more progressive are correctional institutions in Norway, where prison reform has moved away from punitive approaches and has placed rehabilitation and reintegration as a key focus during incarceration.

Eliminating the use of solitary confinement for juveniles is a promising first step towards abolishing the practice entirely. While supporters of solitary may not feel there are effective alternative punishments, human rights advocates continue to fight for prison reform. Looking at solutions used in other countries, perhaps more effective and humane incarceration methods can be realized, and the current paradigm of punishment may shift.

– Stefano Costa, Contributing Writer

Image Credits

Feature: The Euskadi 11 at flickr, Creative Commons

First: Kevin Gessner at flickr, Creative Commons

Second: Hannah at flickr, Creative Commons