Be Good and Don’t Die: Stressors in Child Bereavement

We often forget how important siblings are in our lives. Other than our parents, they have usually known us longer than anyone, playing a central role in our development and shaping many of our early memories. So, when a brother or sister dies, parents and siblings are left reeling and, not surprisingly, mothers and fathers alike notice significant changes in their surviving children. In fact, it is common to see both behavioural and personality changes in bereaved siblings.

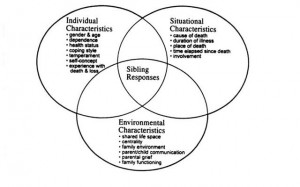

Sibling reaction to the death of a brother or sister depends on a number of variables. It is not only a function of how the loved one died, but also how many other siblings remain in the family, the age and cognitive development of the remaining siblings, as well as other environmental, individual, and situational factors. When a child dies, the surviving children each respond in their own unique way.

The Trauma and Attachment Report had the opportunity to interview clinical psychologist Stephen Fleming, co-author of the 2010 book, Parenting After the Death of a Child: A Practitioner’s Guide. Fleming shared insights on the topic of grief and bereavement in relation to the loss of a sibling, and discussed the added pressures put on bereaved siblings by parents and how these additional pressures impact behaviour.

Fleming: After the death of a child, there is a lot more “focused” stress put on the surviving sibling. After a child dies, parents expect two things from their surviving children: They expect their remaining children to be good – don’t get into trouble, don’t get anyone pregnant and don’t fail academically. Just be good. The second thing parents expect is, don’t die – because if you die, we’ll die. Therefore, surviving siblings are pressured to “be good and don’t die.”

Siblings often report wanting to be good, to stay out of trouble, and to do well in school; they want to please their parents. Children recognize their parent’s altered behaviour as a result of a world that has been dramatically changed. And they do not want to cause further distress for their parents, so they become more cautious regarding what they talk about, when they talk about it, and how they behave.

Fleming: There is often a role reversal, where the child begins looking after their parents. Surviving children may begin feeling as though they have aged ten years in ten minutes. The child is forced to meet the emotional and psychological needs of their parents, a responsibility and added stressor that children usually are not expected to have.

Along with this added responsibility, siblings may feel suffocated by their parents, who may excessively call their children when they are out with friends, they may want to spend a lot of time with them, and frequently ask how they are doing. Not only are surviving children aware of this new overprotective behaviour in their parents, but they try hard to cooperate. Although the surviving siblings want to remain loyal to this parental concern around survival: “be good and don’t die,” they also have a natural desire to lead their own life.

Fleming: The surviving sibling, especially an adolescent, has to juggle their independence and autonomy with their parent’s concern for their survival. Certain behavioural changes seen in the bereaved sibling have to do with this collision of values between parent and child: “be good and don’t die” versus “my older brother could drive at 16, why can’t I?” Siblings tend to be more resilient, wanting to embrace life, while parents tend to grieve longer. This is where the collision happens.

In addition to the attempts made by parents to control and protect their remaining children, they also tend to watch over and survey the surviving child’s behaviour. Not only do parents monitor their child’s behaviour at home, teachers watch over their behaviour and academic performance at school, and coaches monitor their athletic performance. This heavy monitoring can place further stress on the child.

Fleming: That’s the difficult thing for surviving adolescents; they are watched all the time. Although they may be trying hard to move forward, a coach or teacher will notice the sibling isn’t doing so well. Surviving siblings often do not want to admit that they are struggling because they want to meet their parent’s expectations. They don’t want to intensify or add to their parents’ stress.

Stress in surviving siblings not only comes from parents and teachers, but also from their peers. After the death of a brother or sister, siblings do not want to be treated any differently. They want to blend in and not be stigmatized. They don’t want to be thought of as the brother or sister of the deceased, but rather to be acknowledged and known for who they are. When a child returns to school, they do not want to be identified as the sibling who lost their brother or sister in a fatal car accident, but as an individual unto themselves.

Fleming: A very wise adolescent once said to me, “I want the death of my brother to inform my life, not define it.” There is a sense of “I’m not indifferent to the death of my brother, but I do not want it to define my life.”

The death of a child changes the family landscape forever. Parents and siblings respond differently to loss. Parents struggle to meet the parenting needs of the children who remain, while siblings must battle between parents’ expectations and their yearning to live life on their own terms. Surviving siblings are bombarded by added stressors which affect their behaviour. And when behavioural changes in siblings become difficult to manage, seeking professional help may be the next step.

Fleming: Grief is a natural response to loss. Grief is not a pathological phenomenon; it is however the price we pay for loving.

–Tessie Mastorakos, Contributing Writer