The Sex Offender Next Door: Why Re-integration Helps

The release of a sex offender back into a community can be a deeply unnerving experience. Many of us are fearful for our comfort and safety, but attitudes like these may play a role in leading many sex offenders to re-offend.

Sex offenders are faced with multiple challenges upon release. Apart from self-regulation and learning how to control their thoughts and actions, they need to find housing, employment, and most important, a community that will accept and support their continuous rehabilitation.

Sex offenders are not typically strangers lurking in dark alleyways. The perpetrator is often someone the victim knows and trusts. Robin Wilson, professor and program coordinator at the Humber Institute of Technology and Applied Learning, states that relatively few sex crimes, around 23%, involve a stranger previously unknown to the victim. The public has a misguided notion of who the typical sex offender is, and while sexual offender registries are valuable law enforcement tools, there is a growing need for community support.

Wilson considers a best practice approach as involving collaboration between respective operational, professional, and jurisdictional domains. For real rehabilitation to take place, the community must be involved in the process.

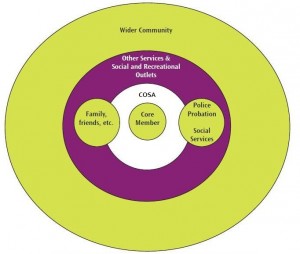

In 1994, the Circles of Support and Accountability (COSA) model of reintegration began after a Canadian Mennonite pastor started a voluntary support group for a repeat sex offender. After almost 20 years in Canada and now functioning internationally, the COSA outlines a restorative approach to the risk management of high-risk ex-offenders, using professionally facilitated volunteerism.

Each ‘Circle’ is made up of a core member (the ex-offender) and four to six community members, individuals who volunteer their time to assist the core member in the community. The program aims to create supportive relationships based on friendship and accountability for behavior –the development of openness among members being a crucial part of the process.

Simply put, ex-offenders are least likely to reoffend when they have ‘friends’ who believe in them.

Wilson found that offenders in COSA had an 83% reduction in sexual recidivism (repeating undesirable and/or criminal behaviours), a 73% reduction in violent recidivism and an overall reduction of 71% in all types of recidivism when compared to the matched non-COSA offenders. His 2012 study shows that community volunteers have an immense impact on improving offenders’ chances for leading normal and productive lives.

Sex offenders are a heterogeneous group, motivated by different factors says Michael Seto, the director of Forensic Rehabilitation Research at the Royal Ottawa Health Care Group. Seto considers that successful reintegration is not simply the absence of further offending. “Successful integration would also mean that the person could live a pro-social, productive life within their circumstances. This might include intimate relationships, stable employment, and positive community ties.”

The success of programs like COSA that work in conjunction with professional treatment programs can be attributed to the continuous re-humanization and the re-moralization of the offender.

Offenders are treated as members of the community and their network of support approaches them without apprehension about the past. Most important, they are given the confidence that they are in control of themselves and that they can choose to behave differently than before.

Seto says that a major obstacle for sex offender treatment is the stigma associated with being labeled a sex offender and being seen forever as high-risk, and that positive social support has a tremendous impact on treatment outcome.

Perhaps most encouraging is the story of a small community in Florida called ‘Miracle Village’, home to over 100 registered sex offenders – none of whom have reoffended. Its residents actively support each other in their attempts to build new lives and work to establish themselves as functioning members of their community.

Of note, the village does not accept those who have been diagnosed with pedophilia or convicted of violent sex crimes against strangers. Some say it is made up of lower risk ex-offenders who are easier to rehabilitate.

Wilson says that offenders targeted for COSA are usually those who have long histories of re-offending, have typically failed in treatment and have displayed intractable antisocial values and attitudes. Stable housing, as well as social support, has shown a relationship to reduced sexual recidivism and criminality among both child molesters and rapists.

The results are compelling: A supportive social network makes a difference. Addressing an offender’s humanity, loneliness, and need for positive relationships has a strong impact.

Still, some sex offenders really are too high-risk to allow back into their communities. Seto says that while “successful reintegration is the aspiration for most sex offenders, some individuals pose such a high risk of re-offending that incapacitation is the only viable option. This can come in the form of long sentences, long term hospitalization, or indefinite sentencing according to (in Canada) Canada’s Dangerous Offender designation.”

Does it all seem too easy? One can’t help but wonder. Then again, shouldn’t it be evident that an approach that shuns and ostracizes is doomed from the start? Can anyone “re-integrate” when viewed as a pariah?

Perhaps the take-home message is about compassion and humanity. And our ability to overcome our insecurities when in the company of those who frighten us.

When Seto was asked whether he truly believes sex offenders can change, he responded “Yes…some of them.”

-Jana Vigor, Contributing Writer