A Hands-On Approach to Psychotherapy?

A friend of mine, Sigourney (name changed), once told me she would never see a therapist who wouldn’t hug her. Adamant that non-sexual touch in therapy helped her feel connected, she characterized a therapist who wouldn’t touch her as rejecting, cold, and untrustworthy.

The subject of non-sexual touch in therapy is controversial, and seems to vary depending on the professional training of the clinician. A study of clinical psychologists by Cheryl Stenzel and Patricia Rupert of Loyola University shows that many practitioners worry touch can be misinterpreted as erotic, or can damage a vulnerable client. There is also the risk of ethical complaints, so most psychologists refrain from touching clients under any circumstances.

In contrast, a summary of research by James Phelan of the American Psychoanalytic Association shows that, in surveys of psychotherapists and social workers, more than 80% touch their clients in non-erotic ways. This touch might include a pat on the arm or back, a side hug, or a full-on embrace.

So, when is touch appropriate in a therapy session?

Little training or discussion exists on therapeutic touch. Students of psychotherapy are often left confused, unsure of how to proceed, and afraid to broach the topic with their supervisors. The ethics code of the American Psychological Association does not prohibit non-sexual touch, while sexual contact, of course, is forbidden. In an interview with the Trauma and Mental Health Report, social worker Cara Grosset, a 20-year practitioner of trauma counselling, says that touching a client depends on the context and the person.

“I work with children and adolescents who have experienced or witnessed severe traumas. They may have discovered a parent who died from suicide or seen their parent killed. If they are sobbing uncontrollably in a session when describing this experience, it seems almost inhuman to not reach out with a comforting and appropriate touch.”

Grosset sees many of her clients in group situations, such as summer camps for grieving youth. In this type of setting, a soothing side hug or pat on the back during a difficult discussion happens publicly, leaving little room for misinterpretation. She has found that these gestures help the healing process.

Another example of successful non-sexual touch happens when Grosset facilitates therapy with children and their parents. Some of her young clients run to her at the beginning of a session to hug her as their parents stand by. An affirming response from Grosset is important for the child to feel nurtured and valued.

But Grosset understands why some therapists are reluctant. Many clients don’t want to be touched, and it’s important to know each person’s boundaries. Touch must be for the client’s sake, not the therapist’s. And when touch helps build connection with the client, it can be a beneficial adjunct to talk therapy.

At the same time, touch can be difficult to navigate in private sessions due to ambiguous professional guidelines and taboos surrounding touch in this type of setting. Grosset’s viewpoints are substantiated by other therapists in qualitative research by Carmel Harrison and colleagues at Bangor University in Wales:

“The values of touch included the ideas that touch could offer clients support, acknowledgement and containment. Despite this, all therapists emphasised the rarity and cautious use of touch in their practice. They discussed touch as being outside the remit of clinicians, and considered how limited discussion and training perpetuated this belief.”

It’s easy to find opposing points of view. Some clients feel that a touch from their therapist increases their self-esteem and enables them to move past feelings of worthlessness. For example, a response to a blog on the website ‘Jung at Heart’ read:

“Twenty years ago, my therapy sessions were, after the first six months to a year, almost always punctuated at the end by a hug. Those hugs saved my young life.”

On the same website, others state that they would feel awkward and violated by a therapist’s touch:

“As a therapy client, I really don’t want my therapist touching me. Not a hug, or a pat of the shoulder, or even a handshake.”

In a 2015 New York Times blog, psychotherapist Hilary Jacobs Hendel explains how she spontaneously hugged a client, but still feels uncomfortable about integrating touch into her practice. Instead, she uses imaginary touch, asking her clients to visualize hugs: “Even when I think a physical hug would be therapeutic, I continue to rely on fantasy.” This unique workaround ties back to concerns of actually touching clients.

The benefit of non-sexual touch in therapy is still open to interpretation. Even though research shows that human touch is important to wellbeing, individual clients and therapists differ greatly in their beliefs on the subject, and risk-management leans toward using it sparingly if at all.

– Lysianne Buie, Contributing Writer

Image Credits

Feature: stux at Pixabay, Creative Commons

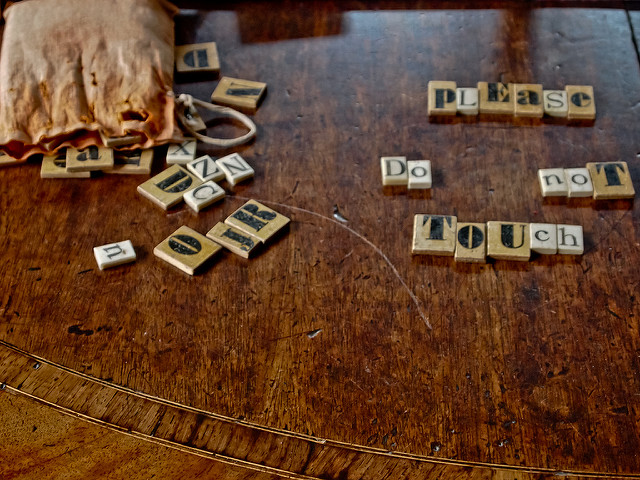

First: Matthew G at flickr, Creative Commons

Second: Amy Wharton at flickr, Creative Commons