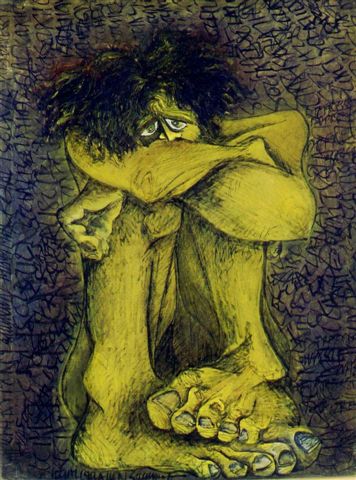

Barriers Prevent Soldiers from Seeking Psychological Help

After two tours of duty in Iraq, Sergeant Eric James of the United States Army returned home to Colorado where he began experiencing symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

James sought out a military psychiatrist for his declining mental health. In over 20 hours of recorded audio, therapists and officers at Fort Carson in Colorado can be heard berating James for suggesting he may be suffering from serious mental illness and ignoring his repeated requests for help. James was told that he was not emotionally crippled because he was “not in a corner rocking back and forth and drooling.”

James’ experience in seeking mental-health treatment may be indicative of a wider, systemic issue within the military. As pleas for help go unanswered, soldiers have begun to actively avoid mental health treatment, fearing consequences like forced retirement or reduced pay.

An article in the The Globe and Mail addressed one of these issues directly:

“Because Canadian Forces members do not earn a pension until they have served 10 years, this encourages some to wait until they’ve reached that milestone before asking the military for mental health counseling and other aid.”

Mental-health programs become inaccessible as soldiers are caught between a desire to seek out support and a fear of losing financial security, potentially losing their livelihood or living with declining mental health.

Worse, a 2012 Harvard Gazette report on the US Military stated that:

“Estimates of PTSD are higher when surveys are anonymous than when they are not anonymous.”

There may be consequences for soldiers who speak up about their mental health issues, and these consequences act as a barrier to seeking help.

It’s also possible that James’ case may be an example of the old “patch ’em up and send ’em back” approach to treating members of the military, whereby doctors and therapists devise a quick fix for physical and mental problems in an effort to get soldiers back into active duty.

Donald (name changed for anonymity), a current member of the Canadian Armed Forces, told the Trauma and Mental Health Report in an interview that painkillers and antidepressants are often prescribed in place of a more comprehensive approach to health concerns. These treatments address symptoms, but not the underlying causes.

Using medications to help sufferers of PTSD manage symptoms is an important aspect of treatment. But if supportive psychotherapy is provided either on its own or alongside drug therapy, the need for medications can be significantly decreased.

A study published with the American Psychiatric Association noted that:

“While treating PTSD with drug therapy has accumulated some empirical support, the Institute of Medicine rates trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy as the only first-level treatment for PTSD.”

And while proper treatment for PTSD is necessary, it can be expensive. An article from the LA Times reported a military estimate of treating PTSD to be $1.5 million over a soldier’s lifetime.

For James, after an internal investigation, he was ultimately sent for treatment and received a medical retirement with benefits. Many of our military personnel receive no treatment at all, leaving them to struggle with PTSD on their own.

– Andrei Nistor, Contributing Writer

Image Credits:

Feature: Paranoid from Suffolk at flickr, Creative Commons

First: Chris Devers at flickr, Creative Commons

Second: Syed Ali Wasif at flickr, Creative Commons