Front Line Healthcare Workers Still Showing Psychological Distress

Thirty-six percent of healthcare workers (HCWs) report thoughts of suicide at some point in their lives, they face more than double the risk of suicide in comparison to the general population. And the suicide rate is 1.5 times higher in male clinicians compared to their female colleagues.

The burden was only heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic with HCWs facing the disease head-on. During the pandemic they worked long hours, often lacked personal protective equipment, saw the worst of the disease, witnessed a high number of deaths of patients under their care, suffered traumatic experiences, and faced ethical dilemmas. Most HCWs often worried about spreading the disease to their loved ones and stayed away from their family during the height of the pandemic. Some HCWs reported sleeping in their garages in fear of bringing the disease home.

As the pandemic went on, the rates of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) increased among physicians as new variants were introduced. PTSD is characterized by feelings of anxiety, depression, insomnia, intrusive thoughts, hyperarousal, and suicidal thoughts and ideations. Those who had a pre-existing mental health condition were at a higher risk of symptoms worsening. Overall, 60% of HCWs stated that the pandemic negatively impacted their mental health.

Moreover, the risk of burnout among physicians has been higher than average for years. The field is known for its long working hours – it is not uncommon for nurses to have 24-hour shifts or be on call. The standard nursing schedule in North America requires that you should hold at least three 12-hour shifts a week, and these often run from 6 am – 6 pm or 6 pm – 6 am. Many nurses complain of inflexible schedules, lack of work-life balance, working overtime, short notice of shift changes, working extra shifts, being on call for floating shifts, and sleep deprivation due to the long working hours. All these factors can contribute to burnout, and if not handled promptly, could lead to an increased risk for depression and anxiety.

Another factor contributing to the decline in mental health is fatigue and moral injury. Moral injury describes how a HCW feels when they cannot meet the standard of care they expect from themselves. This was particularly challenging during the pandemic as staffing shortages, limited medical supplies, and increased hospital admissions meant that HCWs had to partake in “Hallway Medicine”. This describes the rationing of resources, knowing that their decision to save one life meant they were unable to save another.

Despite the increased need for mental health services, in 2021, only 3 in 10 HCWs received mental health services. Why?

There is an underlying expectation in HCWs of placing the well-being of others before themselves. Perhaps admirable, this leads to HCWs lacking the proper care and services they need. HCWs need to seek out support to be able to continue the level of care their patients need.

A barrier to seeking support may mental health stigma among HCWs. This can lead to an over-reliance on HCWs to self-treat and to refrain from using peer support, increasing risk of suicide.

While the worst of the pandemic is seemingly behind us, HCWs are still being impacted by grief, setbacks, and having to rebuild systems. One of the measurable impacts has been the high turnover rates seen during the pandemic. If the trends do not change, more than 6.5 million US healthcare professionals will leave their jobs permanently by 2026, with only 1.9 million replacing them. This will leave about 3.2 million healthcare jobs vacant within the next five years.

With the need for mental health support, resources like FrontLine Connect have been created to mend the gaps in healthcare workers getting the support they need.

Shayla Gerity, a Program Manager within the APAF Center for Workplace Mental Health (the program behind FrontLine Connect), shares that FrontLine Connect is an online toolkit for HCWs’ mental health. The toolkit video provides insights to the barriers faced by HCWs and showcases interviews with experts who are successfully addressing these barriers within their own healthcare systems.

FrontLine Connect is intended for hospital and health system leaders to learn about innovations and success stories from peer institutions that have made mental health services more accessible for their healthcare workforce.

Gerity explains, “[Turnover] is another reason for hospital and health system leaders to seek out mental health resources and implement plans that both prevent and address burnout, mental health issues, and overall well-being”.

Gerity expands on who can use the resource, “While those in leadership roles have the final say in implementing new policies and programs, anyone who works in healthcare or related fields can access the Frontline Toolkit and share it with those who may be able to effect similar change. The toolkit highlights effective strategies for healthcare leaders to improve access to timely and effective mental healthcare, and to eradicate stigma and other barriers. One thing we learned time and time again was that change happens from the top down AND bottom up, meaning that an employee on staff, or a group of medical students speaking up can be the catalyst for leadership implementing change”.

Resources such as FrontLine connect are needed to support the mental health of HCWs and address the barriers HCWs face when accessing support. By shining a light on this issue, hopefully healthcare workers will experience less stigma and seek out the help they need.

-Taylor Alves, Contributing Writer

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is committed to providing individuals in emotional crisis with support, which can include connection to specialized services for different populations. If you are in crisis, please call or text 988 for immediate connection to services.

Image Credits:

Feature: JESHOOTS.COM at Unsplash, Creative Commons

First: Ashkan Forouzani at Unsplash, Creative Commons

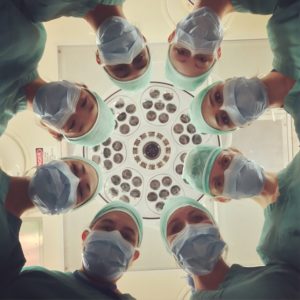

Second: National Cancer Institute at Unsplash, Creative Commons

Moral injury is all too prevalent. Our over-stressed health care workers do need to give themselves permission to seek counseling. When she or he does reach out, consider the possibility it could take weeks or month to locate a therapist who has an opening. There’s a severe shortage of trained counselors.

In 2016 a report on the National Projections of Supply and Demand for Selected Behavioral Health Practitioners projected an estimated shortage of more than 10,000 full-time mental health, substance abuse, and school counselors by 2025 (HRSA Workforce report, Nov., 2016). And these figures did not anticipate increased need due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The explosion of intersecting need begs the question:

who will be available to help the helpers? Efforts must be made to address this issue in order to ensure the highest quality of care for all those in need.