Failed Mental Health App Highlights Pitfalls of Social Media

On October 29, 2014, The Samaritans—a suicide-prevention organization in the United Kingdom—launched an app for Twitter called Samaritans Radar. Its purpose: to detect alarming, depressive, and suicidal tweets to help prevent suicide. Less than a week later, the app was suspended due to public outcry over privacy concerns.

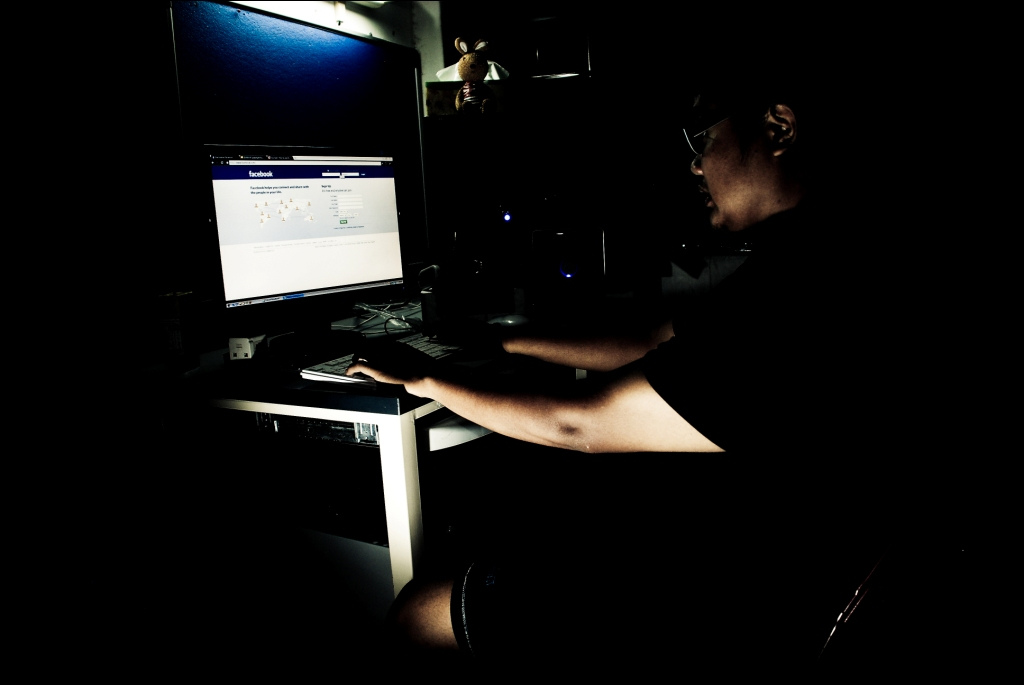

Social media are being used increasingly for marketing and advertising, with privacy a growing issue. Many marketing apps, like Hootsuite, track users’ social media posts in fairly covert ways. Yet, when social media pits privacy against mental health, ethical conflicts are concerning.

Traditionally in mental healthcare, there are few reasons to break confidentiality between client and therapist, such as harm to self or others.

The Samaritans Radar app worked by tracking tweets from every account the individual follows on Twitter. If alarming content was found—ranging from “I’m tired of being alone.” to “Feeling sad.”—the app would notify the user by email. Along with the email, came a link to the flagged tweet, as well as suicide intervention and prevention resources that the individual could provide to the writer of the alarming content.

At the launch of the app, the organization said that:

“Samaritans Radar turns your social net into a safety net by flagging potentially worrying tweets from friends, that you may have missed, giving you the option to reach out and support them.”

The app was quickly criticized for allowing users to track people’s tweets without their awareness or consent. The Samaritans replied by highlighting that everything posted on Twitter and all the information the app uses was public, and that it was up to the app’s user to decide whether they wanted to respond to any particular tweet.

Adrian Short, who started a petition to shut down Samaritans Radar, stated that it “breaches people’s privacy by collecting, processing, and sharing sensitive information about their emotional and mental health status.”

He also noted that the app may be used by less-than-scrupulous individuals for all sorts of purposes, not just helping individuals overcome mental health issues.

The Samaritans addressed these concerns by launching a “white list”, where people could sign up if they wanted to deny the app access to tracking their account. Many did not see this as a solution since opting out would require people to be aware of the app’s existence, leaving privacy in jeopardy.

But the problem that the app was trying to address is not trivial. In the UK, where the Samaritans are based, suicide is the leading cause of death among males under the age of 35. A free mobile app could be an easily accessible way to reach out to people who are alone and lacking other forms of support.

As one of the few supporters of the app, Hannah Jane Parkinson wrote for the Guardian:

“It is estimated that 9.6% of young people aged 5-16 have a clinically recognised mental health condition. Anything that helps to better this situation is great, and particularly as it is crucial to catch mental ill health early on.”

Yet as Adrian Short and others pointed out, this same easy access also poses potential threats. Internet bullying is common, especially among vulnerable users that Samaritans Radar targeted. The app could therefore be used for nefarious purposes.

“The app makes people more vulnerable online. While this could be used legitimately by a friend to offer help, it also gives stalkers and bullies and opportunity to increase their levels of abuse at a time when their targets are especially down,” says Adrian Short.

The app was an attempt to reach out to people in need of emotional support and to raise awareness about mental health using new media. But it highlighted the potential pitfalls of such platforms for dealing with mental health concerns. While the incidence of mental health problems is concerning, putting peoples’ mental health into the hands of anyone with access to a smartphone is naïve.

Perhaps this unsuccessful launch did successfully show that a greater understanding of social media users and platforms is needed before apps like Samaritan Radar can become commonplace.

– Essi Numminen, Contributing Writer

Photo Credits:

Feature: Jayson Lorenzen on Flickr

First: Christoph Spiegl on Flickr

Second: ahmad ridhwan on Flickr