Parkinson’s Takes its Toll on Family Caregivers

Her hands and legs trembled, she could no longer drive. Cognitively, she declined. Her balance was affected, and she often fell. My grandmother Anna (name changed) had Parkinson’s Disease. It took over her life.

As a vibrant and independent woman, Anna had always been eager to help her family. Then, as the disease progressed, roles began to shift, and younger family members had to care for her.

Anna battled Parkinson’s Disease (PD) for more than 15 years. A degenerative neurocognitive condition, it is caused by a gradual loss of dopamine producing cells in the brain that worsens over time leading to tremors, cognitive impairment, and emotional changes.

To date, there is no cure, so a combination of medication and therapy is the only treatment. Anna battled this debilitating illness with no chance of recovery.

As she declined, so did her capacity to be self-sufficient. Her motor abilities drastically decreased, and her memory continued to diminish. She required supervision the majority of the day, and was unable to perform her favorite activities, such as baking, making crafts, sewing, and gardening.

Before Anna was admitted to a long-term facility in 2015, caring for her became a full-time job shared by my mother, my sisters, and grandfather. For my mother Charlotte (name changed), seeing her mother’s deterioration was particularly difficult. Unexpectedly shouldering the role of primary caregiver took a toll:

“At times on my own, I would go in the shower and cry. At other times too, the circumstances made me short and impatient with people. I would be intolerant and lose my temper due to the frustration.”

A study by Laurence Solberg and colleagues examined the emotional and mental health of adult children who are primary caregivers to ill parents. In administering a survey to identify stress levels, the researchers found that caregivers had heightened levels of negative feelings, such as anxiety, while caring for a parent. They found that being a caregiver of an elderly, sick parent adversely affected personal health. However, caregivers balancing the needs of an ill parent with those of their own children did not experience elevated stress compared to individuals without children.

But my own mother’s experience was different. She found it demanding to balance caring for an ill parent and caring for her own children.

“If you only have to balance an elderly parent and a job, it’s much easier than if you also have a family. With children, there’s additional responsibility. Anna required some priority, but I couldn’t lose focus on my children.”

When researchers Caroline Kenny and colleagues examined the experiences of family caregivers, many expressed distress over feeling unprepared for the role. My mother felt the same:

“We didn’t know how to properly care for Anna. We didn’t know how to lift her correctly, or how to deal with her frustration. On top of having the responsibility of caring for her, we had the added stress of not knowing how to handle her properly.”

And finding time for herself was not easy for my mother either. Solberg’s research supports this predicament: three quarters of caregivers reported decreased time for personal hobbies and interests. Charlotte said:

“I do think these responsibilities cause you to neglect your usual pastimes. I went from work to Anna’s home to my home. There wasn’t time for myself.”

In a study by Vasiliki Orgeta and colleagues, published in the International Psychogeriatrics Journal, the authors reported on the importance of social support for coping with the strain of becoming a caregiver.

For me, it was painful to see my grandmother’s decline alongside my own mother’s struggle to care for her. But consistent with Orgeta’s findings, I’ve found that relying on friends and family, and my social support system, has helped alleviate the anxiety of seeing my family in distress.

No one’s experience is the same; people cope in their own ways. For my mother, the situation has been heartbreaking:

“Seeing a person who is loving and vibrant, such a nurturing mother, become a person who is not nurturing anymore, not strong, whether emotionally or physically, is agonizing. It’s a part of life, but it’s hard to accept.”

– Alyssa Carvajal, Contributing Writer

Image Credits

Feature: Lesia Szyca, Trauma and Mental Health Report Artist, used with permission

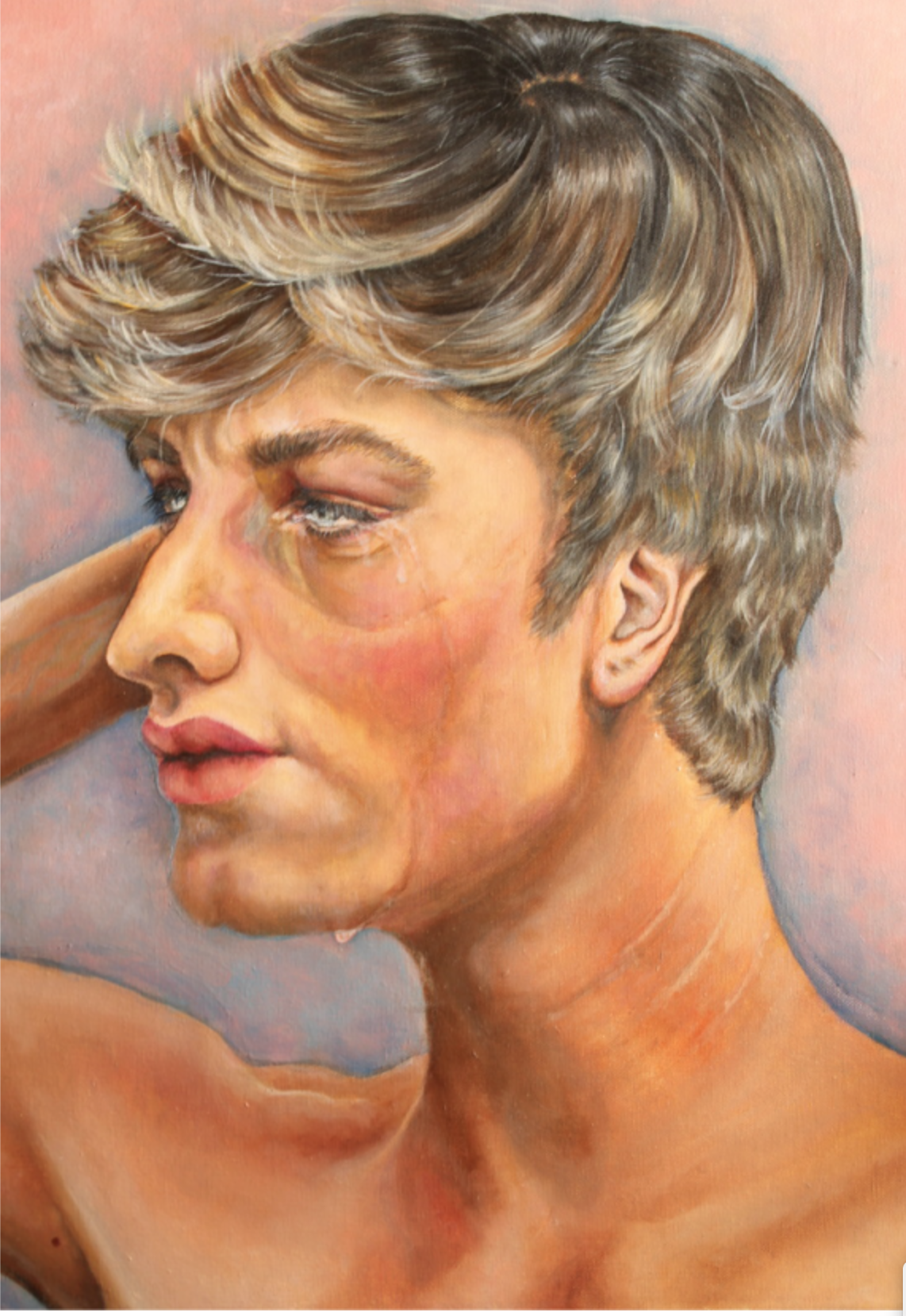

First: Lesia Szyca, Trauma and Mental Health Report Artist, used with permission

Second: Lesia Szyca, Trauma and Mental Health Report Artist, used with permission